“I Can’t Wait Until He Goes to Hell.”

After the verdict, Sonya Massey's family showed up at the press conference to rebuke the system, just like their daughter did before a cop shot her in the face.

They showed up different this time.

On the heels of the verdict that found former deputy Sean Grayson guilty of second-degree murder in the killing of Sonya Massey, her family arrived at the post-verdict press conference not to beg, not to forgive, not to show grace, and not to hold hands with the state that destroyed them. They named evil, rebuked it, and wished death on it.

They stood there, shoulder to shoulder, breathing fire through microphones that have too often been used to sanctify Black pain and absolution. And this time, it was the men, her father and cousin, who mostly took the lead.

It’s rare to see that.

The family moved as one body. Sonya’s father, James Wilburn, took the mic with a grief that did not ask permission. He named skin color and justice in the same breath. “There’s a difference when you have my skin color and Grayson’s skin color,” he said, and you could hear the generations behind that sentence.

Then he landed the line that should be carved into the courthouse steps: “Sean Grayson should be able to get out of jail when my daughter can get out of that burial vault and walk out of Oak Hill Cemetery.”

Black fathers are rarely allowed to speak their grief publicly. When they do, they’re expected to be stoic, strong, composed, quietly dignified, never raw. But James Wilburn broke that containment. His sentence was both logic and lament, built like scripture and wound like a threat. He made clear made clear that there is no equivalence between a man losing his freedom and a father losing his child.

That line was a refusal of parity, a rejection of the false moral symmetry that so often governs how America talks about racial violence. It exposed how punishment in this system is always finite for the white perpetrator and infinite for the Black family. The officer will serve his time, appeal his sentence, one day walk free. Sonya Massey will remain in the ground. Her father will remain in mourning. Wilburn’s words turned that imbalance into an indictment.

For a Black father to say it, in public, is especially powerful because this nation has long waged war on the very image of Black fatherhood. It has painted Black men as absent, negligent, violent, unfit to protect or nurture. Wilburn’s statement obliterated that lie in a single breath. It was the voice of a father who showed up, who named his daughter’s worth, and who demanded that the state see what it destroyed. It was the voice of a man asserting both his humanity and his authority against a system designed to deny him both.

When he said his daughter would have to rise from her vault before Grayson deserved release, he was speaking metaphysically but also politically. He was collapsing the gap between personal loss and systemic critique. It meant: You don’t get to walk free while my child is buried. You don’t get redemption until we get resurrection. It was not just about one man’s punishment, it was about the permanence of loss and the impossibility of closure under white supremacy.

In that moment, James Wilburn wasn’t pleading for justice, he was defining it. He was telling the country that until it can bring back what it keeps destroying, it has no right to ask Black people to move on.

Then came her cousin, Sontae with his broad chest and strong back. He didn’t come to translate pain into policy talk. He came to tell the truth in its native tongue. “I’m fueled by rage right now,” he said.

Because what else do you call it when an officer announces, on camera, I’ll shoot you in the face, and then does exactly that, and a jury still chooses the smaller box? He turned to a reporter and answered his question with a question: “How would you feel if your child was shot in the face and they came back with a second-degree conviction?”

There’s no neat answer to that. There shouldn’t be.

Someone else at the presser invoked the officer’s cancer and said, in essence, that god had visited that disease upon him. You might think that was brutal. But it was also a declaration that if earthly scales refuse to balance, there is a higher court keeping receipts.

For once, the theological burden didn’t fall on the family to offer absolution, it fell on the state and its servants to face judgment. That reversal matters. Too often Christianity is used to tranquilize Black grief. We gotta forgive, be patient, and wait on the Lord while the machinery of violence keeps humming. But the Massey family turned that weaponized theology around and used the language of faith as a cudgel against the structure that stole their loved one.

But first let me say that the men did not hover in the background as stoic props to a performance of dignity. They stepped forward and spoke with disciplined rage, not to overshadow the mother but to echo and amplify her. In the American imagination, Black men are too often cast as either threat or absence, as furious or mute. Yesterday, they were neither. They were present. They were clear. They were morally articulate. The optics of Black mourning shifted before our eyes. We didn’t see a lone mother carrying the nation’s expectations of saintliness, but a family arrayed like a choir, each voice taking a verse, the refrain unflinching.

We’ve become accustomed to the choreography of Black mourning where we usually see a mother clutching a photo, a sister collapsing into a relative’s arms, and the press conference gets framed as an altar of restraint and grace. The performance of Black civility in the face of carnage has been demanded of us for decades. Meanwhile, somewhere a pastor is asked to pray for calm and healing before the body has even cooled.

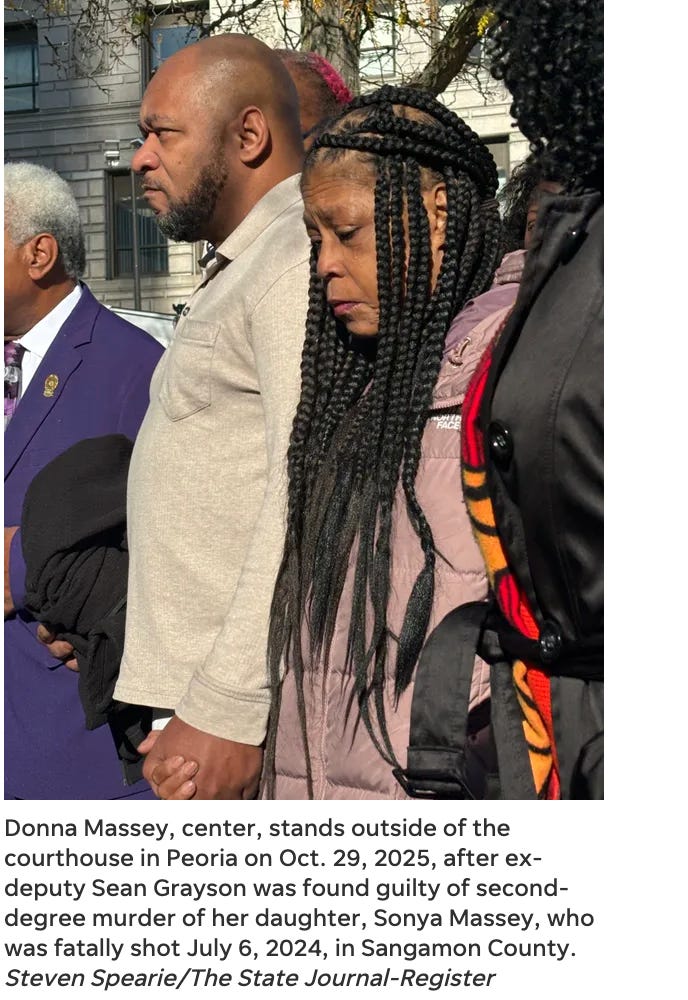

But Donna Massey offered a benediction of refusal.

There was no preface. No appeasement. No ritual of thank-yous to the same institutions that failed her daughter. She looked straight into the public square and said what so many Black families have been coached not to say out loud: “Anybody who watched the video and thinks that it was partly Sonya’s fault is inhumane.”

By calling anyone who blamed her daughter inhumane, she defended her daughter and indicted the entire moral logic that keeps demanding that Black death be reasonable, excusable, or somehow self-inflicted. She was rejected the country’s favorite lie: that every murdered Black person must share some portion of the blame for their own death.

Then she delivered this line that lit up my entire soul: “For them not to give him life, and Sonya got life—and death…I can’t wait until he goes to hell.” Wheww, my god today, Y’all.

“I can’t wait until he goes to hell.”

The significance of a Black mother saying she hopes a white cop goes to hell cannot be overstated. When she said those words, she was doing something far more profound than venting rage. She was flipping the entire moral hierarchy that has governed how Black grief is supposed to sound in public.

In this country, Black mothers are expected to cry, to forgive, to turn the other cheek so America can feel good about itself again. Their pain becomes a kind of moral currency and proof that they are still decent, still human, still capable of love in a system built to crush them.

America loves the spectacle of the forgiving Black mother because it restores its sense of moral order. It lets white folks cry, nod, and feel redeemed without changing a damn thing. But this mother refused to baptize the system that murdered her child. Her words cut against centuries of expectation, against every news segment that praises “grace under pressure.”

Donna Massey refused that bargain. She didn’t offer grace. She offered truth. She chose to be honest. She didn’t sanctify her daughter’s murder with forgiveness. She didn’t soothe the conscience of the people who need Black grace more than they deserve it.

When Donna Massey said she couldn’t wait for her daughter’s killer to go to hell, she wasn’t just talking about one man’s soul. No y’all. She was calling out the theology that built this nation’s racial conscience. Her fury was devotional. It was spiritual warfare waged in public. She flipped the script of Christian endurance and hurled it back at the structure that created it, saying in effect: If there is a hell, then it was made for men like him and for the racist system that protects them.

That moment cracked the ritual of Black mourning wide open. It reminded us that not all prayers are meant to soothe. Some are meant to summon judgment.

“I can’t wait until he goes to hell” was theology repurposed. It was a Black woman reclaiming divine judgment from a country that keeps pretending it owns God. In a courtroom that downgraded her daughter’s worth to second-degree, she invoked a higher court, one not swayed by whiteness, power, or precedent. She was saying: if this world refuses to deliver justice, then let there be another realm where justice is not negotiable.

Her use of “can’t wait” is the incision point! It’s the place where grief turns into defiance. She didn’t say “he deserves to go to hell” or “he’s going to hell someday.” She said “I can’t wait.” That phrase collapses the distance between now and judgment. It drags eternity into the present tense.

In those two words, “can’t wait,” she turned passive belief into active desire. It’s the difference between acceptance and impatience, between resignation and revolt. She was refusing to let justice remain theoretical or postponed to the afterlife. Her language said: I want to see the scales balanced. I want to live long enough to witness the reckoning this system keeps delaying.

And that impatience matters, y’all. Black people have been told for generations to wait. Wait, for the courts. Wait, for the reforms. Wait, for heaven. Wait, for white America to grow a conscience. Every Black mother who has buried a child because of this system has been expected to wait her way through the pain. Donna Massey’s can’t wait shattered that theology of delay. We’ve waited long enough.

In a country that keeps extending grace to white killers and postponing justice for the dead, “can’t wait” becomes both prayer and protest. And, it’s prophetic. It’s a mother demanding acceleration. It’s a refusal to let the slow machinery of “justice” grind her daughter’s memory into dust.

So when she said “I can’t wait until he goes to hell,” she was naming the sacred impatience of the oppressed. She was saying that the reckoning doesn’t belong to history, or to god alone. It belongs to right now.

This Black mother’s words were also ancestral.

Black people have always known that this system is not where our deliverance lives. From the spirituals that sang of chariots swinging low to the whispered prayers over lynched bodies, there’s a lineage of hope that the wicked will one day meet what they’ve earned. When Donna Massey said she can’t wait for him to go to hell, she was standing in that tradition and naming what so many Black mothers before her have swallowed in silence.

What she did was radical because it stripped away the illusion that forgiveness is the only moral posture available to the oppressed. Her words insisted that anger, too, can be holy. That wanting justice, even brutal, divine justice, can be an act of love for the one you lost.

In that moment, Donna Massey wasn’t just condemning a man. She was condemning a world that keeps demanding Black grace as the price of white comfort. And by doing so, she reminded us that sometimes the holiest thing a mother can do is stop praying for her enemy’s salvation, and start declaring the hell they’ve earned.

If this piece moved you, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your $8 subscription doesn’t just keep my Substack fueled and independent, it helps me buy HBCU journalism students textbooks, cameras, laptops, software, pay for their travel for reporting trips, cover conference registrations, and emergency funds for food and fees.

This piece is blistering, necessary, and unflinching. Thank you for writing it.

What you’ve laid bare isn’t just personal rage, it’s a systemic indictment.

The U.S. justice system doesn’t fail by accident. It fails by design.

It protects predators, punishes truth-tellers, and ritualizes cruelty as procedure.

This man deserves whatever reckoning awaits him—-not out of vengeance, but because justice, if it means anything, must account for harm.

And yet we know: in this country, justice is often a performance, not a principle.

Your voice cuts through that farce.

It doesn’t ask for permission.

It doesn’t wait for consensus.

It names what others flinch from.

This isn’t just catharsis. It’s clarity.

And it’s exactly what this moment demands.

I will also say, my wife and I have been reading your pieces and sharing them religiously; thank you for speaking truth to power!

—Johan

Professor of Behavioral Economics & Applied Cognitive Theory

Former Foreign Service Officer

I love this. And I'm so proud of the Massey family. It seems many black people are waking up and realizing that being nice to the system isn't getting us anywhere. You are so right about America needing black grace so they don't feel bad about themselves. When black people pronounce judgment on this system and country, I've noticed it scares people. Because if anyone has a legitimate right to call for the end of this system, it's black people. They're so used to us being ok with crumbs, and we're not taking it anymore.